Rastafari

Rastafari interestingly is one of the most well documented cultural phenomena to have emerged in the last century. Interestingly though, this documentation is not by us; it’s not by West Indians. The experts so to speak on Rastafari reside in Washington, Haig, UK; there is even a Rastafari expert on Rastafarian music in Japan, a woman called Yashiko Shibata who did her work the 80’s; quite a while back and in a sense I and I, Afrikans, black people, Jamaicans, Caribbean persons have been slow in really looking deeply at his movement and trying to interpret and explain it.

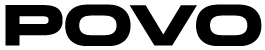

So my work in particular tried to make sense of Rastafari in my space and my life and one of my earliest insights was that Rastafari in Jamaica constructed and operated out of a poverty laboratory. So poverty is our common unifier; this is the space that Rastafari is most dominant in and within those spaces, Rastafari is the salvation of those spaces; key leader, key teacher, key father of the fatherless. So my work then sought to make sense of Rastafari to Jamaican society.

What is the role and place of this movement? Many people tend to focus on Rastafari aesthetics; dread locks, idea of herb and gunja, the image and veneration of his Majesty, as our divine inspiration. But what has the movement done within the context that it exists.

In my assessment, Rastafari has been the key decolonising tool; decolonising voice; decolonising facility and in this respect, I think, this is where Rastafari becomes a platform for an international collaboration, international expansion and the appeal that we see that makes Rastafari potent Afrikan diaspora contributions that we have now.

In looking at the movement in the context of Jamaica, we can’t do that without looking historically. Historically based on the colonial experience, the Afrikan male was completely marginalised or erased from the domestic states. Our histories; our families; our day to day existence are driven through the work of the mother and the focus on the mother. So, mothers given our society have a measure of respect, perhaps not as much as they ought to have but they have the respect from having been historically present and historically, the source that keeps the children going.

If you are to talk to one in three Jamaicans they don’t have a connection to their father. Many of them don’t know their father. Many of them claim that it is only through Rastafari that they have known what fatherhood is or what a father is. So in my mind, Rastafari becomes the surrogate father for the society. It’s the father that most of the Jamaican society did not have. Within the Jamaican conscious, Rastafari is considered to be primarily a male dominated movement and based on the latest statistics that we have seen from government census, the movement is 85% male, in Jamaica that is. This is slightly different outside of Jamaica and in some places like Trinidad and Tobago, it’s almost 50/50 which is unusual and we have not really had any studies to tell us why Trinidad might be so different from Jamaica. But within this male fraternity, bredren are developed into what I would describe as responsible Afrikan males. So, the understanding of self; the understanding of father; the understanding of man with woman is therefore shaped and driven by the intervention of Rastafari in the society.

Now in our day to day lives in Jamaica, what we experience is Rastafari holding Afrika in front of the society and asking; what of this our dominant ancestry. Jamaican society like many of the world’s colonised spaces was very keen on demonstrating that it was civilised at independence and what civilised meant was to have a seamless transmission from British colonial rule to independence and some of our leaders like Norman Manley bragged that we really altered very little in becoming independent and not recognising by that admission that really what you have done is preserve the colonial society with all the injuries that it would impose and inflict on the Afrikan.

It is Rastafari through decades of agitation starting with Leonard Howell that brings in to our thinking and our consciousness, the view of Afrika and also, this is developed from the platform which was established by Marcus Garvey. In a sense Rastafari becomes a practical application of Garvey but anchored through the incarnation and crownation of his majesty Emperor Haile Selassie. So the Emperor comes and becomes that father that most Jamaicans never had and the instructions from within the movement therefore, were directing the attention of those who don’t know what a father look like to the example provided by the Emperor of Ethiopia.

Over the decades, the movement has developed a number of different kinds of reputation and I’m not going to talk about gunja because everyone is clear about that but I would like to talk about how it has vocalised the world and expanded its range.

I mentioned one of my earliest ancestors, as poverty laboratory well, out of this very poor completely marginalised space; Rastafari found a way of communicating with the world and this was through the construction of reggae music. In some peoples’ definition, reggae music is the king’s music and there are those who say that reggae emerges in Jamaica after the visit of his Imperial Majesty in 1966 and in a sense becomes a kind of medium left by his Majesty to help us in our hardships. Reggae therefore becomes one of the chief sources of earnings for most Rastafarian; and you know the example of Bob Marley and others who became multi-millionaires through that work. But outside its profitability, reggae is really that medium through which the message has been transmitted and even in Rastafari there are tensions about the value and importance of reggae that no-one can deny that it has performed in the global world. For the poor Rastafari, reggae is commercial music while in Nyabingi it’s spiritual music but you won’t get to Nyabingi unless you are in that space locally and able to experience it in a ritual context. So reggae in its range of forms becomes the food that is generally offered but we are really saying that coming to the Nyabingi as well to get the deeper spirituality that

Rastafari holds.

Over the years there have been many individuals who have used dreadlocks and the medium of reggae as a way of gaining fame and fortune and I think it is out of that space that a lot of the confusion; a lot of the misrepresentation of Rastafari as a spirituality develops.

Reggae and dancehall are linked but they are linked more through space than through substance. So dancehall originally really referred to the very same spaces that reggae was performed in but with persons like U-Roy emerging, he became the first of a series of individuals to take to not take things expansive production of lyrics but more the repetitious toasting style. So U-Roy, he’s a father of a certain genre of Jamaican music; really brings into being what is now the popular expression of

dancehall music.

From 1981 when Bob Marley passed on those who are critical musicologist would say that, that was the demise of reggae coming at that point. With Marley’s passing, dancehall became the popular song coming out of Jamaica with people like King Yellow Man representing the genre. With that shift from the focus on reggae, the analysts have also said that we moved from culture to what is commonly described as ‘slackness’ music, by ‘slackness’, we are talking about body parts and violence; and a range of conversations that were not necessarily driven in the Pan-Afrikan uplifting tradition, solidarity among people who are struggling, etc.

Dancehall has a distinct genre; starts after the death of Bob Marley and with that some say through various kinds of conspiracy theory, it was really an attempt to remove the potency of what reggae had produced at that point. Zimbabwe is a classic example of reggae solidarity and potency of that media. Bob Marley’s participation in that struggle popularised Zimbabwe in a way that no other Afrikan country has a reputation in the West Indies. That’s part of the struggle where we come from. We don’t have a connection with Afrika in a normal and day to day way and it was Marley’s bridge that helped us to think about our common struggle as a people across the Atlantic.

From ’81 up until present there has been a range of attempts to critique dancehall music and even ascribed it as being one of the sources of what they call social and cultural decay. Recently, the Ministry of National Security in Jamaica produced some statistics on crime and violence in Jamaica. Among the Caribbean nations, Jamaica leads in violence. It’s not just gun crimes but there is also road fatalities and a range of hopelessness that young people face. I’m commonly referred to as elder and I have been called elder for the past 10 years but that is partially due to the fact that many young people will not pass 25, especially those who live in urban communities. So there is a high attrition, especially for young males who are the most vulnerable on the front line.

What we have seen therefore is that in the communities’ spaces, the youth are under siege and some people say that this is because of dancehall. There are artists who come with a badness, in fact, dancehall has a few key signifiers. One is that you have to have a girls tune; you have to have a gun tune; you have to have a herb tune and this is a recipe for your success. Now if you come on stage and you don’t get a forward, you draw for one of those tunes and you are assured that the audience will raise up, etc. In sense then there has been an embrace of the ‘slackness’ that dancehall purports and young people in particular are most at risk in absorbing this without questioning. Many of the young people today; many of you are quite aware of some of the conditions based on the way the media has handled it. Public spaces become transformed because of the involvement of music. Bus stops, bus terminals, passenger buses; we’ve had to impose very strong legislation about noise pollution and we have strict night noise Acts because of the way dancehall has encroached across the society. Some people feel confronted or offended by it.

But in a sense Jamaica understands dancehall as being specific to a space and specific to a time. This is not necessarily the case in other Caribbean Islands where you will have dancehall music with bad words and explicit content in the public domain. So, within the Caribbean there is a tension therefore that Jamaican cultural influence could produce, the civil societies that Cayman and Barbados in particular have had strong legislations banning it and this is also affiliated to things outside of dancehall; drug trafficking, etc.

So what I’m therefore saying is that between the emergence of reggae in 1966 and the death of Bob Marley in 1981 there are those who feel that there has been a conspiracy to remove this vocal Pan-Afrikan media out of the scene and promoters and record publishers have supported the ‘slackness’ and in some instances they have given preference to artists who produce this kind of music than those who are trying to sing uplifting songs, you know, they will say ‘well there is no money for that’ they will just say that ‘the people want this’, without necessarily taking responsibility for what the people

are supplying.